Life is Getting more Equitable but also Harder For Female Carers

From Invisible Labor to Just Visibly Burdened?

Women’s History Month came to a close a couple weeks ago, the social media posts trickled off, and I found myself reflecting on what has materially changed for women - during my lifetime, and particularly through the lens of care. I also started, and planned to publish, this newsletter in March to align with Women’s History Month. But it turns out that grief is a jerk, and I’ve been letting myself ride the rollercoaster of emotions rather than writing about them. Alas, there’s no reason why women’s history and equity should be relegated to one month - we talk about it year-round over here!

When I’ve shared that its a struggle these days to find a nanny under $30/hour, my mom - who was a single working parent - is always flabbergasted and tells me that she easily found babysitters who were “thrilled” to be earning a few bucks an hour, even to care for my disabled brother. There’s a lot to unpack in that assertion, but regardless it is well documented that the care marketplace, particularly on the supply side, has changed pretty drastically. The burden on female caregivers in many ways feels like it’s become much heavier since we were the kids. At that same time, it’s wild to think that less than a decade before my mom was hiring said babysitters, she didn’t have the legal right to apply for credit in her own name.

The pandemic drew a line in the sand when it comes to care. The burden shouldered by caregivers, women especially, became much more visible and openly talked about. Of course, it was already steadily getting harder to find and pay for child and elder care, but it took a global pandemic to begin to expose the unfair burden that society places on both paid and unpaid caregivers, the majority of whom are women. Terms like “invisible labor,” “mental load,” and “weaponized incompetence“ are now more mainstream.

A lot has changed, for better and worse. I thought I’d take a look at the specific changes that have impacted women caregivers between when many of us were growing up in the 1970s, to now, when many of us are raising kids of our own and/or caring for elders.

Time use - paid work vs. household and care labor: Men are doing slightly more of the unpaid and household and care work than they were in the 1970s, but women are doing significantly more paid work, and more often the “breadwinner” than they were in the 1970s. However, women still do much more unpaid household work than men, even when they engage in paid work, and even when they are they are the household breadwinner.

Labor force participation and earnings: Women’s wages represented 64% of men’s in 1980, reached 77% in 2000, but has made little progress and hovers around 80% more than 20 years later. Households in the 1970s with children could live comfortably on the equivalent of one middle class salary. This is not true today, where a family of four must make $275k or more to live comfortably in many US cities, despite a median salary of just over $92k.

Caregiver market: caregivers could afford to live in the places where they worked, and there wasn’t a care shortage as there is today. There are many reasons behind this; one of course being that caregiving is not valued in a capitalist society, but also that women (and teenage girls) who worked as caregivers in the 1970s were seen as bringing in “extra” income, rather than needing to earn a living wage. Likewise, parents could afford childcare if they needed it - but the cost of childcare has increased an incomprehensible 2,000% since the 1970s.

Parents are doing more overall: Parents were historically more likely to have help from other relatives, rather than providing care to aging parents. But not only that: we are expected to do a hell of a lot more for our kids than our parents were! There were not the same pressures to sign kids up for a slew of enrichment activities, public schools were better funded to provide the education (and child care) we needed, kids walked outside alone and no parents were shamed, parents didn’t worry about mass shootings. I have started talking to my 10 year old about taking small steps toward more independence, and my 6 year old shared that his teacher told him it was “illegal” to leave a kid under 11 home alone (it’s not, but people act like it is).1

If we look at all of these changes together, on the positive side, women are earning more, and are more financially independent. There are more protections for women to dissuade financial discrimination, and we are therefore also relatively less susceptible to household discrimination and inequities now than we were 50 years ago. While still not available to most, the normalization of more flexible work has been instrumental for women who are also caregivers, and will hopefully continue to expand in creative ways. These are the good things!

On the other hand, we didn’t have the same “market failures” and demands on our time when it came to caregiving. The increased financial independence has not been met with an equal allocation of unpaid household and care duties, meaning women work more and are afforded less free time. While caregiver burdens are more recognized, and there is (somewhat) greater equality between the work women and men do in and out of the home, and the expectations of what we do as parents overall has increased with fewer and more scarce options for support. We’re also more likely to be caring for elders and children at the same time. So there’s been a shifting around of burdens, but not an acknowledgement as a society that care is the work that makes all other work possible - and a critical factor in gender equity.

There are some interesting trends that reflect this tension. For example, there is some speculation that more families are swinging back to opting for single earner households. This may work great for some, but it’s not for everyone, nor is it financially feasible or desirable for most. It’s also just not good for business. I cringe whenever I see reference to the “tradwives” that are all over social media, including the stories from ex-tradwives who have found themselves without credit history, job experience and helpless when their marriage goes sideways. On the other hand, more women are opting out of marriage altogether, and more people are choosing not to have children. Are these the extremes we’re supposed to choose between when our society refuses to value care?

And so, it remains true that Women Still Can’t Have it All. But as Anne Marie-Slaughter also affirmed, it is possible. I still want it all! While the pandemic did spur a major positive shift in one important area she emphasized in that article over a decade ago - flexibility of when and where we get work done - the most important challenge to tackle next is finding a way to create societal value and support system for carers.

Recent Wins

President’s SOTU focused on care. Biden highlighted the need to overhaul our care infrastructure in his State of the Union, and again in a speech on April 9.

“President Biden’s third State of the Union Address asked us to imagine a future with affordable child care, paid leave, aging and disability care, especially in the home. He affirmed the unprecedented focus and commitment of this administration to supporting caregiving – both those who need it and those who provide it.” — Ai-Jen Poo, Executive Director, Caring Across Generations

The White House also released a Fact Sheet of ‘Actions on care’ planned for this month. The focus is on support for childcare businesses - most of which are run by women. I have to admit I was glad to see this if also a tad underwhelmed, as this doesn’t address the much bigger and more systemic issues at play. Hopefully this is just the tip of the iceberg.

Supporting Womens’ Health. Jill Biden announced $100 million in funding for women’s health research, then pledged an additional $200 million for sexual and reproductive health. Health is inextricably linked to care, and women do the majority of caregiving, yet research on women’s health has been historically underfunded - as have female founders, health company and otherwise. I have to believe that this will absolutely impact care.

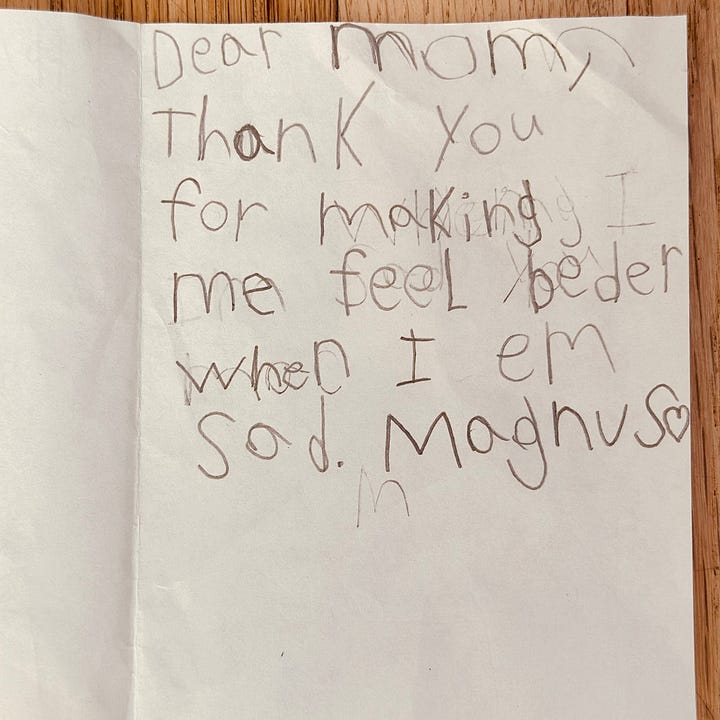

Raising Feminist boys. In general I always feel like wishing women “happy women’s day” once a year precisely because of the fact that we’ve been historically, and continue to be marginalized just seems… weird? Is it just me? But I’ll make an exception for my six year old who made me this card, and gave it to me on International Women’s Day eve (he simply couldn’t wait). More important than wishing me a happy day, he told me that he learned about suffragettes at school and made the astute observation that “not allowing women to vote was dumb.”

I’ll leave with you with some fun feminist recommendations and as usual, some good caregiving reads. Let me know your thoughts, ideas, stories - I’m here for it all.

xoxo

A few favorite feminist Substackistas

Lyz - Men Yell at Me

Jessica Valenti - Abortion, Every Day

Josie Cox - Women | Money |Power

Anniki Sommerville - ‘Midlifing it’

A Gen Xandwich feminist playlist

📚 Reads

Don’t Tell America the Babysitter’s Dead. The place to start on the interesting conversation around the disappearance of teen babysitters.

The Problem with ‘Affordable’ Childcare. Spoiler alert: it should be free.

The Rise of ‘Carefluencers’. People are sharing and documenting their care experiences on social media, providing an outlet and sense of community, but also questions about consent.

There’s no age limit in WA, but apparently several US states do have laws - in Illinois you can’t leave a child under 14 home alone! I definitely babysat other kids when I was younger than 14. Lots of interesting commentary on the topic of teen babysitters (and lack thereof) floating around right now. In addition to the Atlantic article linked above, see Anne Helen Petersen’s recent piece.

I hear you on the grief front, and I am right there alongside you on how important it is to raise awareness about the inequality in caregiving. Great article, Anna.

Grief is such a jerk!